PCOS in Teens

Experiencing acne?

Missing a period or two?

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in reproductive-aged women including teens! Now before you roll your eyes and utter the sentence, "I don't have cysts on my ovaries," please note you don't need to have cysts in order to have PCOS (I'll talk about that below).

PCOS is a collection of symptoms - both visual (like acne) and diagnostic (like serum testosterone). It's also a diagnosis of exclusion among other androgen (male hormone) excess disorder. In teens, PCOS may present differently than it would in adults.

PCOS Criteria in Teens

To be diagnosed with PCOS, you must have 2 out of 3 criteria, as defined by the Rotterdam Criteria. Criteria includes:

-

Delayed ovulation or irregular menstrual cycles (anovulation)

-

High androgenic hormones like testosterone

-

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound

In teens however, both irregular menstrual cycles and hight androgens are required. Ultrasound is not recommended for diagnosis.

High Androgens (aka. hyperandrogenism)

What's are androgens? It's a group of male hormones which are present in females. The most common one is testosterone. When androgen levels are high in the body, it can lead to some unwanted symptoms.

High androgens are the most common criteria seen in teens, because it includes clinical signs like acne and/or hirsutism (male-pattern hair growth) - caused by, you guessed it, high testosterone levels.

But, just because you see a couple of zits or see some hair - it doesn't mean you have PCOS.

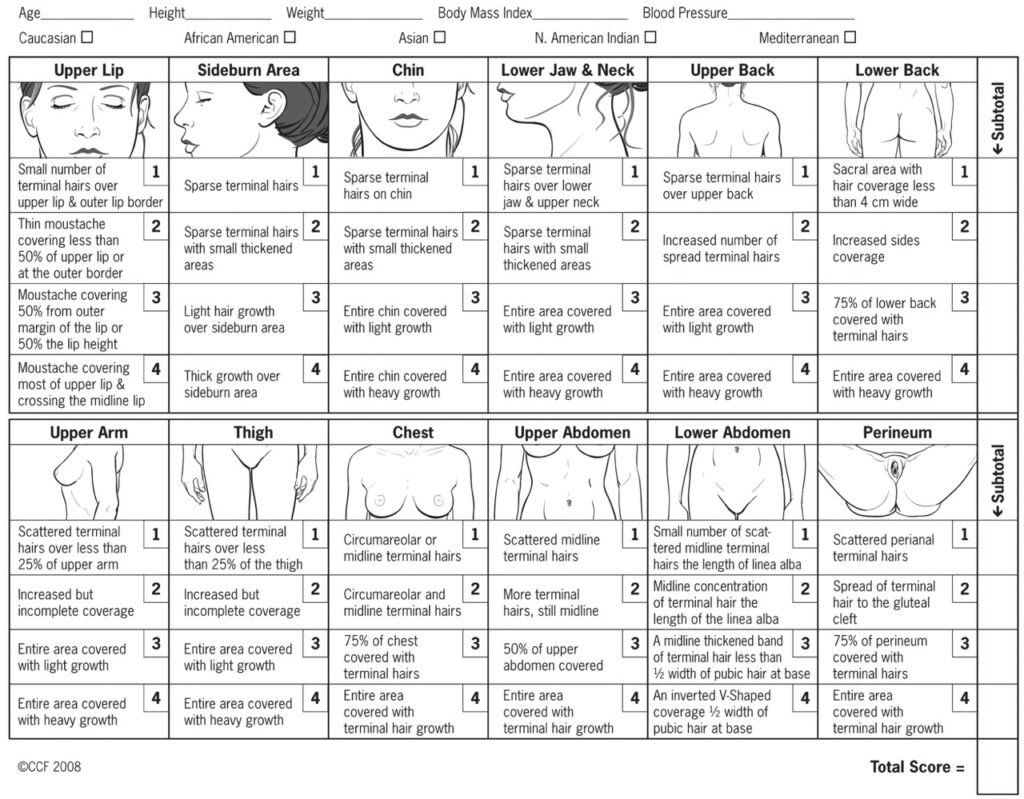

We're talking about moderate-severe acne (ex. more than 11 red zits on your face) that isn't affected by topical medications. When it comes to hair, you need to score between 4-6 on the modified Ferriman-Gallwey chart. One thing to note is that some ethnicities present with more hair growth, which should be factored in when calculating the score.

You may also notice hair loss, around the frontal area (ie. where your bangs would be), and that can also be a sign of high testosterone.

Another way to determine if you have high androgens (like testosterone) is by testing them. A simple blood test will suffice (no need for the fancy tests) and can be done anytime during your cycle. Shortly after your period begins, serum testosterone reaches adult levels.

Androgens that you may want to get tested include:

-

Total testosterone

-

Free testosterone

-

DHEA

-

Androstenedione

-

Sex Hormone Binding Globulin

Irregular Periods

Period length can actually vary based on when you first experience menstruation. Irregular cycles are defined as:

-

Normal in the first year of having your period

-

In the first 1-3 years of having your period: Less than 21 or greater than 45 days

-

After having your period for 3 years: Less than 21or greater than 35 days

-

After having your period for 3 years: Less than 8 menstrual cycles per year

Moreover, when you first start getting your period, it's highly likely that you won't be ovulating. Approximately 85% of menstrual cycles (in the first year of your period) are ovulatory. Six year in, only 25% of your cycles will be anovulatory (aka. no ovulation is happening).

Within the first 2 years after your period starts, you may notice period irregularities and anovulation - and that's okay!

Polycystic Ovaries

In case you missed it, you don't need to have polycystic ovaries to have PCOS. In fact, the ASRM guidelines state that ultrasound should not be used for diagnosis in women who have had their period for less than 8 years because ovaries tend to have lots of follicles during this time.

So what does that mean? You need to rely on the other 2 criteria to figure out if you have PCOS.

Conventional Treatments of PCOS

It's likely that if you go to your medical doctor, they'll tell you to take the birth control pill. The pill is considered the first line of treatment. You may hear that the pill will regulate your cycle, but it will actually shut down your body's natural hormones and replace them with the hormones in the pill - which may be a synthetic estrogen and progestin (depending on which you take). Periods that you experience while on the pill, aren't true periods at all - they are simple withdrawal bleeds from the hormones.

Here's the thing. If you think of the pill as a bandaid, you won't know if these symptoms are just going to come back once you stop the it. Most women stop the pill around the time they're ready to start thinking of having kids. But if PCOS is still looming in the background, it may lead to fertility issues down the line.

Something that you should also be aware of is that severe anxiety and depression is higher in adults with PCOS. And it's likely also increased in teens. A huge study in 2016 investigated different types of birth control and how they were associated with antidepressants and a diagnosis of depression. Researchers found that teens (between 15 to 19) are more sensitive to depressive symptoms and antidepressants than adults. This was seen when teens were using the combined pill and progestin-only pill. The study did show that the incidence of depression and antidepressants use decreased with age.

Birth control is not always bad, it's provided choice and reproductive freedom to many, but it's important to recognize why you're taking, and understanding the risks associated with it as well.

Approaching PCOS Naturally

When we're dealing with PCOS in teens we want to do a couple of things:

-

Promote a regular menstrual cycle

-

Restore natural ovulation

-

Reduce/get rid of acne and hirsutism

-

Achieve weight loss if necessary (because this may lead to conditions like diabetes)

Yes, there are supplements you can take to help with the above four goals. But one of the main priorities is to promote a healthy diet and exercise in ALL teens with PCOS. I go into that more in previous articles, so please check those out. These have widespread effects in optimizing hormonal outcomes, general health and quality of life.

This doesn't mean you should be eating salads and hopping on a treadmill ASAP though. It's important to take stock of your daily or weekly routine and see which changes can be made. Making some goals, writing things down (ex. a diet and exercise diary, as long as it's not leading to eating disorder tendencies), problem solving with a parent or health professional, etc.

Taking things slow is okay. Starting small is okay. One of my favourite quotes (that I usually see when I make a cup of tea) is "The creating of a thousand forests is in one acorn."

Exercise and PCOS

Exercise guidelines are different between adults and teens. You should be aiming for at least 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity, including activities that strengthen muscle and bone at least 3 times weekly. Group classes can be helpful, because of the social and community aspect.

Examples of exercises that specifically strengthen muscle and bone are:

-

Dancing

-

HIIT workouts

-

Hiking

-

Jogging/running

-

Jumping Rope

-

Stair climbing

-

Tennis

For more info on exercise and PCOS, check out my previous article here.

Next Steps

Now that you’re familiar on how PCOS is presented in teens, here’s what you can do next:

-

Track your cycle length

-

Pay attention to any clinical signs, such as acne or hair growth

-

Get your blood work done (PS. NDs can order your blood work too!

Once you have these, figure out how you want to approach the solution. Will it be birth control or focusing on the root of the issue?

Now that you have a solid plan, please sign up for my monthly newsletter called The Flow for more informative and useful content like this! I want to make sure that you have a good flow!

References

Teede, H., Misso, M., Costello, M., Dokras, A., Laven, J., Moran, L., Piltonen, T., Norman, R., Andersen, M., Azziz, R., Balen, A., Baye, E., Boyle, J., Brennan, L., Broekmans, F., Dabadghao, P., Devoto, L., Dewailly, D., Downes, L., Fauser, B., Franks, S., Garad, R., Gibson-Helm, M., Harrison, C., Hart, R., Hawkes, R., Hirschberg, A., Hoeger, K., Hohmann, F., Hutchison, S., Joham, A., Johnson, L., Jordan, C., Kulkarni, J., Legro, R., Li, R., Lujan, M., Malhotra, J., Mansfield, D., Marsh, K., McAllister, V., Mocanu, E., Mol, B., Ng, E., Oberfield, S., Ottey, S., Peña, A., Qiao, J., Redman, L., Rodgers, R., Rombauts, L., Romualdi, D., Shah, D., Speight, J., Spritzer, P., Stener-Victorin, E., Stepto, N., Tapanainen, J., Tassone, E., Thangaratinam, S., Thondan, M., Tzeng, C., van der Spuy, Z., Vanky, E., Vogiatzi, M., Wan, A., Wijeyaratne, C., Witchel, S., Woolcock, J. and Yildiz, B. (2018). Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility, 110(3), pp.364-379.

Peña, A. and Metz, M. (2017). What is adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome?. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 54(4), pp.351-355.

Rothenberg, S., Beverley, R., Barnard, E., Baradaran-Shoraka, M. and Sanfilippo, J. (2018). Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 48, pp.103-114.